An engineer from the Mumbai Municipal Coporation has discovered a plan and details for Metro in Mumbai proposed by engineering legend Sir Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya, whose birthday is celebrated every year as Engineer’s Day.

The dream of having an underground railway network in Mumbai is a century old. Nearly a hundred years ago, the city dreamt of what is today a living, breathing reality — a modern underground metro. And it was proposed by none other than engineering legend Sir Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya, who is regarded in India as one of the foremost civil engineers whose birthday, 15 September, is celebrated every year as Engineer’s Day in India, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania.

Post-independence it was BEST’s General Manager PG Patankar who made a plan for a 31.9km underground metro with the help of the Japanese that included a network of five interconnected underground metro lines with a circular route through south Mumbai’s Fort area. Where Sir Visvesvaraya once proposed a 12 km loop, and Patankar a multi-line underground network, both were shelved — largely due to financial constraints, lack of institutional support, and political hesitation.

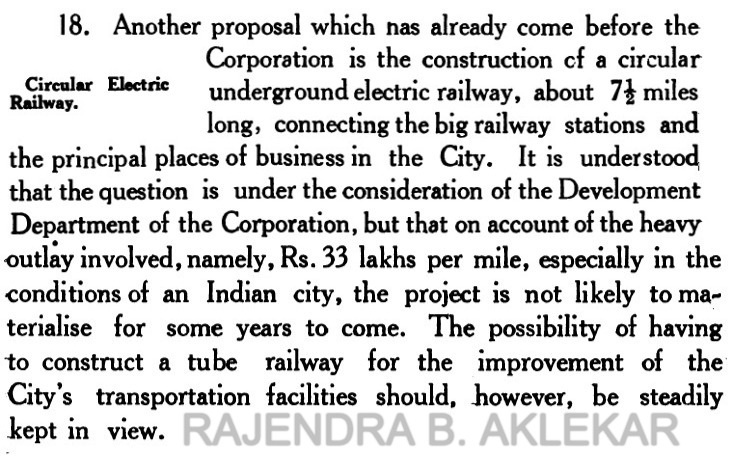

Talking on Sir Visvesvaraya plan, BMC’s executive engineer with heritage conservation department Sanjay Adhav said he came across this startling find buried in the 1924 report titled ‘Municipal Retrenchment and Reform’ prepared by Sir Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya. An astonishing proposal of a 7½-mile-long circular underground electric railway, connecting the island city’s busiest railway stations and commercial hubs.

The cost was staggering for its time — ₹33 lakh per mile — and the project was shelved as “unlikely to materialise for some years to come”. Yet, the foresight is remarkable. The report compares Bombay’s congested rail and road corridors to London, New York, Berlin, and Tokyo, noting how those cities had already taken their tracks underground or elevated to beat traffic snarls.

“I found the treasure in 2023 when there was a proposal to name one of the BMC buildings at the Worli Engineering Hub after Visvesvaraya sir. I dug out data to find out if he was involved in any works with the BMC. It all revealed that he had worked Sir Visvesvaraya as with the retrenchment committee member and was asked to prepare proposals for reduction of expenditure and for reforms needed to secure greater efficiency and economy in the Municipal administration post the first World War. And as the new Aqua Line opens, it is exactly a century now. What coincidence,” an excited Adhav said.

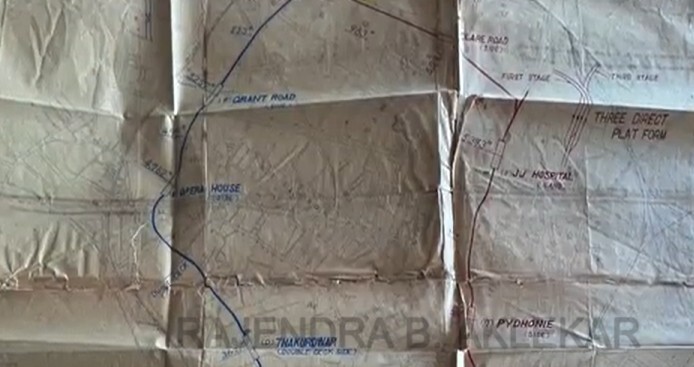

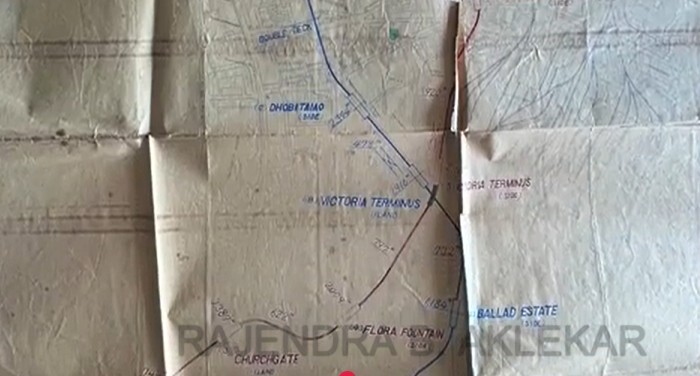

The vision was clear: a rapid transit system beneath the crowded bazaar streets, linking Churchgate, Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus), the docks, and Fort’s business houses. The problem was money, and perhaps a lack of political will. The Great Depression and then the War years buried the idea deeper than any tunnel.

The century-old report also worried about overcrowding, housing, and suburban growth, stressing that only cheap and rapid transit could save Bombay from choking. It was a vision modelled on London’s Tubes and Berlin’s U-Bahn.

But with municipal debts mounting and ₹33 lakh per mile deemed astronomical, the scheme was quietly set aside. The idea was shelved. Bombay carried on with trams, then double-decker buses, then suburban trains groaning under impossible loads. Wars came and went, plans were drawn and abandoned, and the city grew northward without ever digging beneath its crowded streets. The idea, however, did not die. It slept in archives.

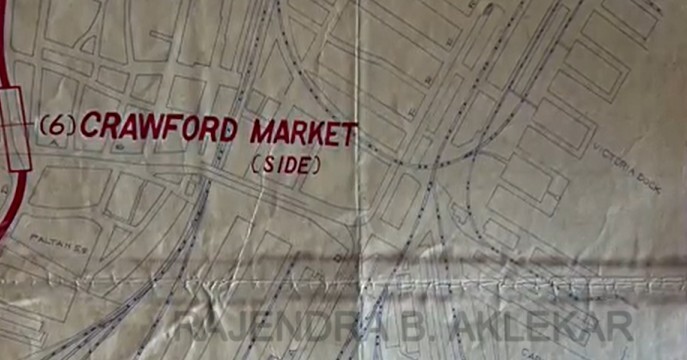

Three decades later, independent India looked again at rapid transit. In 1957, a detailed proposal for a Mumbai Metro system was prepared, pushed by BEST General Manager PG Patankar. This one suggested a 22-km underground corridor linking Colaba, Fort, Marine Lines, and the northern stretches. Engineers studied traffic growth, housing pressure, and suburban congestion, concluding that without an underground railway, Bombay’s future would choke and made a “metro blueprint”. Patankar’s plan was bold: he proposed a network of five interconnected underground metro lines for the island city, totaling about 31.9 km. His design included: a circular route through South Bombay’s Fort area, starting and ending at Victoria Terminus (VT / CSMT). Radial lines connecting VT to Byculla, from Byculla to Sion (east), and Byculla to Mahim (west). With provisions to extend the network outward later, as suburban expansion proceeded.

In his preface, Patankar argued that by 1963, Bombay (then limited to island plus immediate suburbs) had a population of about 4.2 million and was already experiencing serious vehicle congestion. He noted that vehicle numbers had soared from ~13,400 in 1955 to over 93,400 by 1962. He insisted that rapid underground transit was “unavoidable” if the city were to cope. He also addressed technical challenges: tunnel ventilation, structural underpinning of buildings, signalling, the dimensions of rolling stock, and how to maintain surface stability in areas above the tunnels. Patankar even framed an additional rationale: in times of war or air raids, an underground network would afford better protection to citizens than surface transport.

For cost comparisons, he estimated the project in the 1960s would cost about Rs 17.50 lakh per km — much lower than what had been assumed in overseas projects then. Yet despite the technical maturity and the seriousness of his proposal, Patankar’s scheme was not adopted. But India of the 1950-60s was resource-scarce, and still battling basic developmental challenges. The project was deemed too expensive. Like its 1924 predecessor, it was shelved — largely due to financial constraints, lack of institutional support, and political hesitation. Patankar continued his career with BEST and beyond.

Today in 2025, as Mumbai runs Aqua Line 3 — a fully underground 33.5 km metro corridor — the city is living the ghost of the idea of finally laying down the steel, tunnels, stations and systems that those earlier visionaries had only sketched.

“Being part of the realisation of the dream of underground railway in Mumbai envisaged by none other than Sir Visvesvraya in 1924 and then by Dr P G Patankar in 1958 is a great privilege and fortune of me and my team in MMRC. We lived this dream for past 10 years and did not leave a single stone unturned to make it a reality for Mumbaikars. I cherish each and every moment of this journey full of hope and aspirations, hard work and passion. There were high points and low points but ultimately with the support of Mumbai citizens we could make it possible,” managing director of MMRCL who spearheaded the complex underground metro project Ashwini Bhide told this writer.