We seem to be getting back to the original 1853 blueprint of the railways in India that Lord Dalhousie had proposed. A dear old friend Mrityunjay Bose tagged me in his post of a cute, little old steam locomotive placed on a pedestal at the Boat Club Bhopal during his recent visit. (https://x.com/rajtoday/status/1827772127325442174)

Basic information about it revealed that the old steam loco was named ‘Hill Stallion’ and it was installed by the Bhopal Municipal Corporation and the Indian Railways a few years ago. The loco is about 48 years old and built by the Tata Engineering & Locomotive Company (Telco) and during its lifetime had run on various railways for 34 years, including the Northeastern Railway in Assam. Also, it is a YG class locomotive, which means it used to run on Metre Gauge, a unique 1 m gauge, which is (3 ft 3 3/8 inches) and that set me thinking.

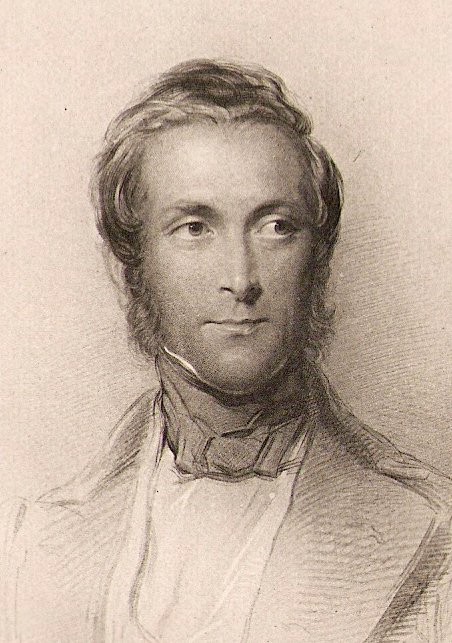

Lord Dalhousie- By George Richmond – Taken from The Life of the Marquess of Dalhousie, K.T., by Sir William Lee-Warner, K.C.S.I., London, 1904, vol.1, frontespiece. Out of copyright., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25522015

It reminded me of Richard Southwell Bourke, the 6th Earl of Mayo, who was the Viceroy of India between 1869–1872, popularly known as Lord Mayo. It was him who had first championed the metric system and pushed for the meter gauge on railways in India. The meter gauge was narrower than the widely accepted Indian broad gauge of 5 feet six inches width.

The story goes that Lord Dalhousie — 36-year-old James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, more popular as the Earl of Dalhousie or simply Lord Dalhousie — who had taken over as India’s youngest Governor General in 1848 had convinced the British government in India to introduce railways through his famous Railway minute of 1853. He had originally proposed a 6 feet gauge for railways in India. During the subsequent debates, however, the Court of Directors of East India Company were in favour of the British 4 ft. 8.1/2-inch gauge.

That apart, Dalhousie wanted a single gauge. He was a strong proponent of a single gauge for the country. In his famous minute, he categorically made it a point to avoid the “evil” of having different gauges to avoid a repetition of what was happening back in England with discontinuous travel.

East India Railway’s Consulting Engineer FW Simms suggested a gauge which was neither British standard gauge of 4 ft. 8.1/2-inch gauge (which was slowly by then getting universal) or the wider seven feet gauge of the Great Western Railway engineered by the prolific Isambard Kingdom Brunel in the same country. He chose something in the middle which was 5 feet six-inch gauge, citing stability of the train and the engine while running and for sturdiness during winds and cyclones. The Court of Directors finally agreed to a gauge of 5 ft 6 in. as the most suitable and this was adopted as the national gauge in India and this ‘middle gauge’ of 5 feet 6 inches that is now called the Indian broad gauge and has become a standard in India.

Lord Dalhousie left India in 1856, soon thereafter began the correspondence regarding adoption and advantages of narrower gauges in India. In 1861, during the Viceroyalty of Lord Canning, the Public Works Department prepared a long note recommending a narrower gauge. While the Government of India was of the firm opinion to permit construction of rail-lines only on 5 ft 6 in. gauge, adhering to Dalhousie’s minute, the 1860s saw a strong lobby for advocating narrow gauge lines.

It was the private lines that took the lead. The Maharaja Sayajirao Khanderao Gaekwad, Ruler of Vadodara, was the first who decided to go for a lighter and narrower gauge. He built a 20-mile-long line from Dabhoi, an important trading centre of his State with Miyagam, a station on the Bombay Baroda and Central India (BB&CI), main-line. It was initially drawn by a pair of oxen, subsequently steam engine was introduced in 1873. The smaller lines slowly started coming up due to ease of construction and financial constraints. These secondary lines, as proposed, were very extensive, and formed systems in themselves. The Government of India concluded that substantially built narrow gauge lines were all that were necessary. It was in the 1870, after careful analysis of the situation, Lord Mayo, a proponent of the metric system, considered that 3 ft 3 in. gauge was the best gauge for the secondary network of railways in India.

By 1950s after the British left India, 46 per cent of the railway track was in the Indian broad gauge, 44 per cent in metre gauge and for the rest there were narrower gauges of 2′-6” and 2′-0”. (March 1952 data). Indian Railways decided to switch mode and launched ‘Project Unigauge’ on April 1, 1992, a single gauge for ease of travel and to develop the backward regions and connect important places. A single gauge and, as Dalhousie wrote, to the removal of ‘evil’ of multiple gauges. The project has come a long way today and as of 2024, we have about 97 pc of railway track in the Indian broad gauge. In the process, we have stripped off all the narrower gauges, their heritage and history.

That loco quietly standing at the Boat Club in Bhopal which Mrityunjay sent me is a sad testimony of one of such ‘killing of the evil’ and the loss of those smaller gauges. But that’s what the ‘Father of Indian Railways’ Lord Dalhousie always wanted, a single gauge the sub-continent. So Indian Railways is now living his dream. May his soul rest in peace.